Flatbush Fights Against Gentrification and Hate amidst BK's Lowest Crime Rates Ever

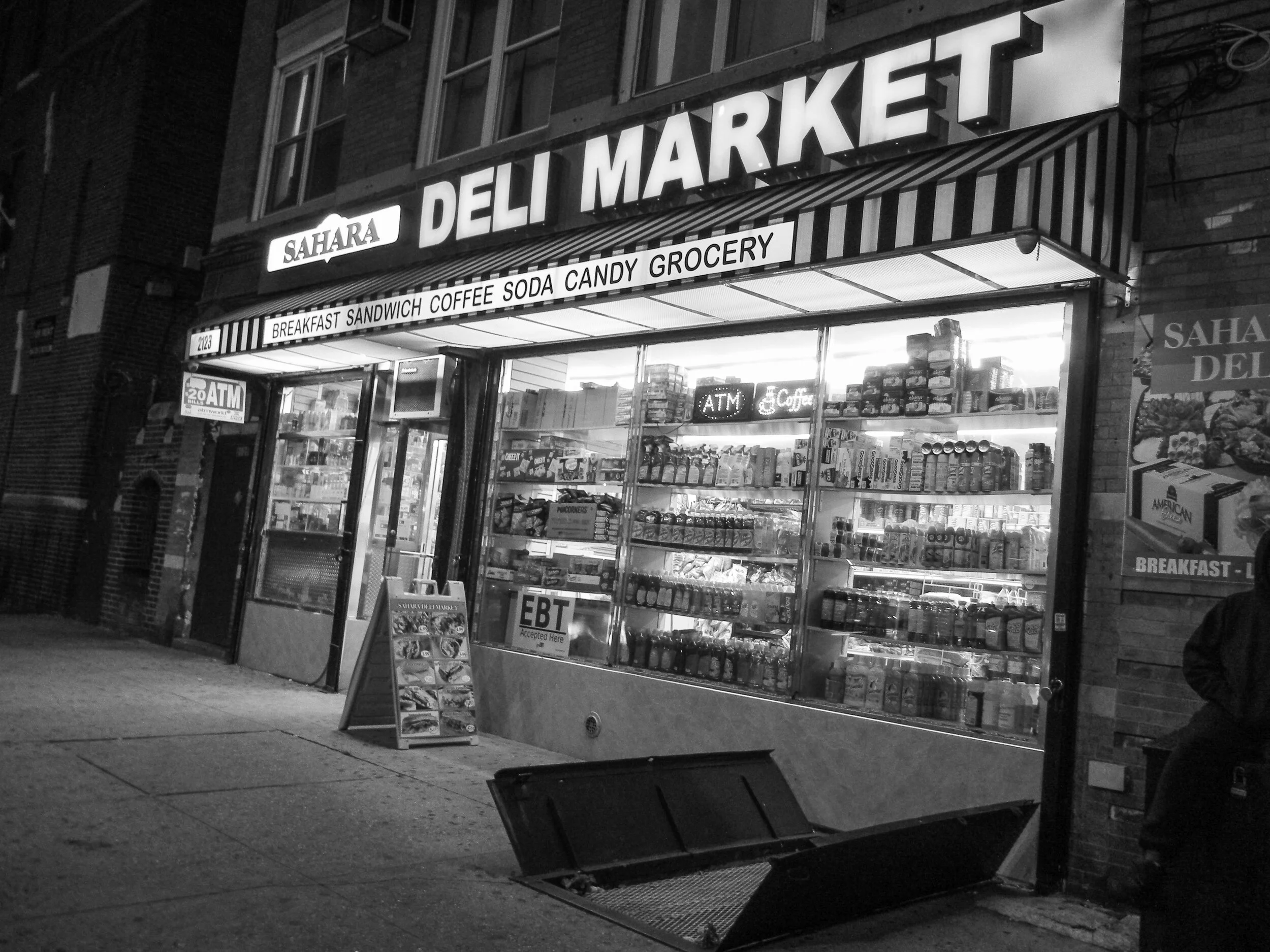

Sahara Deli Market in Flatbush | Carolyn Adams

Violent crime is at an all-time low in once-notoriously gritty Brooklyn, but the number of hate crimes has continued to rise, according to data from the New York Police Department (NYPD).

A series of high-profile bias incidents in Flatbush over the last few months have pushed local government and community members to action in order to reverse the trend. More than two-thirds of the hate crimes in Brooklyn have been anti-Semitic or homophobic in nature, but incidents targeting black people have increased over the last year and account for 14 percent of those reported in Brooklyn.

Brooklyn District Attorney Eric Gonzalez formed a designated Hate Crime Bureau last month, in order to better handle cases and work with communities to prevent them. In a statement, he said, “Protecting everyone in Brooklyn is my highest priority and it is simply unacceptable that members of certain protected groups are fearful to walk the streets of our borough.”

Equality For Flatbush founder Imani Henry expressed skepticism about hate crime legislation, pointing to the treatment of Ann Marie Washington after she was assaulted and stabbed by a white man at the Church Avenue train station in November. “The NYPD wanted to put that out as a robbery and the community fought back instantly. Black women, in particular, have been at the forefront of the struggle and made it abundantly clear that this was not a robbery. It was a misogynistic, racist attack.”

Flatbush is one of the most ethnically-diverse neighborhoods in the city, but Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams organized “a community conversation on diversity and respect” in October, days after the ‘#CornerstoreCaroline’ incident went viral.

Filmed by a bystander, the video showed 53-year-old Teresa Sue Klein making a scene after accusing a 9-year-old black boy of sexually assaulting her at Sahara Deli and escalating it by calling 911, a decision that can have deadly consequences for black people.

'Take It Back Before It's Gone' t-shirt of a protester at the Brooklyn March Against Gentrification, Racism, and Police Violence | Carolyn Adams

The number of quality-of-life complaints to 311 has almost tripled in Flatbush since 2010, which correlates with neighborhood rent increases of more than 37 percent, but many new residents have made non-emergency calls to 911 instead.

According to Senator Kevin S. Parker’s office, there has been a marked increase in the number of such calls, with more than 10,000 citywide in the last year. “We should be making disincentives in our state law for people who want to abuse and weaponize the 911 system.” His proposed legislation, senate bill S9150, would designate non-emergency calls to 911 as misdemeanors and result in a $900 fine or 3 months in prison if violated.

Some community members pointed to gentrification directly as an aggravator of tensions in rapidly-changing neighborhoods like Flatbush. “When we put a bunch of people in a melting pot without a proper understanding or ways to relate to each another, we get anti-black rhetoric and behavior projected onto us and our children,” said Jade Arrindell, a Brooklyn-based educator and community advocate.

Imani Henry said that some of the division has been provoked by landlords who have pitted black, Jewish, and other residents against each other, in order to push tenants out. While black and brown communities are disproportionately affected by gentrification, “it is also impacting Jewish people as well. I think it’s important to talk about the ways that people are being pitted against each other and the ways that it hurts all of us differently.”

Rallying signage at the Brooklyn March Against Gentrification, Racism, and Police Violence | Carolyn Adams

Housing crime has also increased by 18 percent over the last year. Lifelong Flatbush resident Anthony Beckford described Flatbush as “the last stronghold” as residents in other Brooklyn neighborhoods have been pushed out completely. He said that legislation can help to reduce bias incidents, but that well-meaning white newcomers must do their part.

He suggested that they take a stand by refusing to pay inflated rent costs when natives in the same building pay far less. “Just because you can afford more than other families doesn’t mean that you’re better than us. It just means that you have a privilege that we don’t have. You’re being used as a tool in this war against the black and brown people.”

Imani Henry said that despite tensions, there is solidarity between people of all backgrounds and other boroughs that goes unnoticed. “Bedbugs, the lack of extermination, the elevator being out brings tenants together.”

Alexis Blecher, a Flatbush newcomer, attended the Brooklyn March Against Gentrification, Racism, and Police Violence in October and lamenting her role in the gentrification of the neighborhood. She said that it was important that other new residents listen to and support longtime residents. “This is their home. It’s not mine.”

As one of the organizers for the march, Henry repeated that people from all walks need to stand together to combat hate and displacement in Brooklyn. “The diversity that is in our neighborhoods will not survive because gentrification will come for all of us.”